Long-time Chaplin collaborator, Roland 'Rollie' Totheroh recalls, years later, the daring process of editing The Kid during the legal battle of Chaplin's divorce from Mildred Harris.

During the Harris divorce we had to get out of town because they were attaching all of Charlie’s assets. I was living on Highland Avenue with my son and wife and about 3 o’clock in the morning, someone knocked on the front door. Lo and behold, standing out there was Mr. Reeves, who was our manager at the time. He said, “Rollie, come on. We have to get out of town. Use a fictitious name.” I asked him if I could take my assistant, Jack Wilson, along with me and he said yes. “But get right over to the studio and get ahold of the carpenter and have everything crated.” I knew trouble was brewing. We didn’t know where we were going but we had to get ahold of Tom Harrington, who was supposed to have the tickets. So Jack and I went down to the Sant Fe depot after we got all the film of The Kid packed in coffee tins, in two-hundred-foot rolls, loose all the way packed solid on top; there were about 12 cases of it all in negative. And Charlie was at the depot. He had his black glasses on but he had taken off his disguise. He was sitting at the table just about to be waited on and this little kid sitting at the table across the way said “Charlie Chaplin! Charlie Chaplin!” So we had to beat it out of there.

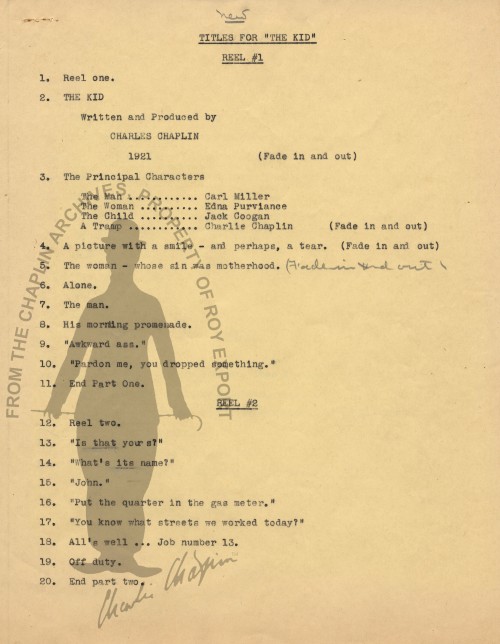

We worked about two weeks in this hotel in Salt Lake City. Charlie was busy selecting titles and different things. Then we got the word that we’d have to move. Charlie said, “I don’t want to know anything about travelling.” He had everything he had in one bag, a black bag; and I called it “the black bag.”

We had to stop over in Chicago before we went to New York. From New York I thought we would have our passports and go to Europe if we could get out of the country without being detected, which was pretty hard for Charlie to do. Before the train came in he said, “Put that bag between your legs, Rollie. Don’t let anybody near it.” I knew he had valuables in it, but he had everything he had in there – all these cash bonds and everything else.

We got to New York, and he went to see his lawyer right away. It was up to me to find a laboratory. Jack Wilson knew Dave Horsley, one of the pioneers of the motion picture business and he had studios over in Bayonne, New Jersey. The studios weren’t active then. We got ahold of Horsley and he said, “Sure.” So to cover up, we had a sign printed, and we called it the “Blue Moon Film Company.” We hung it outside the studio when we got on the truck that had our film on it, it was the busy time of the day, and we were crossing the river going over to New Jersey. I could smell the fumes from the nitrate but I didn’t realize what it was. I had a hunch that the vibrations could raise hell with us. Anyhow, when I opened a lot of tins – especially the ones at the bottom of the tins – they were just ready to explode. Supposing they would have exploded on the ferry-boats; I had them marked “Machine Tools”! We didn’t go to bed night or day. They had built some shelves for us to lay out all the films, all the negatives; I forget how many hundreds of thousands of scenes we had. I would send Jack out to a delicatessen to get food and he got some mosquito netting so we wouldn’t get stung by all those darn moquitoes. I finished about two reels; Tom Harrington used to come over and I’d give him a reel at a time.

One night I came outside to get a breath of fresh air and there were two guys standing out there, Italian looking guys. They said, “You have Chaplin’s film here, we know that. You can make yourself $30,000. All you have to do is keep the vault unlocked and we’ll take care of the rest of it.” So I told them that all we had there was work-print. I said, “We don’t have the negative, the stuff is probably in the vaults in New York.” After that, of course, we got a couple of guards to stand watch. And I never saw those two guys again.

(Roland 'Rollie' Totheroh interviewed by Timothy J. Lyons, "Film Culture", Spring 1972)