On September 26th, 1925 at 7:30 pm, BBC radio transmitted to every station throughout the British Isles a ten-minute excerpt from the screening of a silent film, an experiment that proved to be a historic moment in film and broadcasting history. What the BBC listeners heard that evening was “a storm of uncontrolled laughter, inspired by the only man in the world who could make people laugh continually for the space of five minutes, viz., Charlie Chaplin” from a screening at London’s Tivoli Theatre of his latest film, The Gold Rush. Detailed descriptions of the fits of laughter were subsequently recounted in the press:

Amongst the audience members who attended the Tivoli Theatre premiere of Chaplin’s “great new film” a few days earlier were Mr. and Mrs. Winston Churchill, as reported on September 27th in the British Sunday newspaper, People. The journalist suggests that if Churchill “can impart some of Charlie’s spirit and cheerfulness into the coming Parliamentary Session he may do a lot to lessen the tension of the many political problems.”

This is the earliest mention we have of Churchill in the Chaplin archives. According to Chaplin’s autobiography, the two men first met four years later, in September 1929, at a party at Marion Davies's beach-house: “About fifty guests were milling about between the ballroom and the reception room when [Churchill] appeared in the doorway with [William Randolph] Hearst and stood Napoleon-like with his hand in his waistcoat, watching the dancing. He seemed lost and out of place. W.R. saw me and beckoned me over and we were introduced.” At first, as they engaged in small talk, Chaplin found Churchill abrupt, but when Chaplin mentioned the English Labour Government, Churchill suddenly brightened up. Chaplin recalled:

“‘What I don't understand,’ I said, ‘is that in England the election of a socialist government does not alter the status of a king and queen.’ [Churchill’s] glance was quick and humourously challenging. ‘Of course not,’ he said.

‘I thought socialists were opposed to a monarchy.’

He laughed. ‘If you were in England we'd cut your head off for that remark.’

An evening or so later he invited me to dinner in his suite at the hotel. Two other guests were there, also his son Randolph, a handsome stripling of sixteen, who was esurient for intellectual argument and had the criticism of intolerant youth. I could see that Winston was very proud of him. It was a delightful evening in which father and son bantered about inconsequential things. We met several times after that at Marion's beach-house before he returned to England.”

On September 24, 1929, Churchill, accompanied by Randolph Churchill, John Churchill, John Churchill Jr., and Ambassador Alexander Moore, visited Chaplin at his Los Angeles studios where they witnessed the filming of City Lights. Chaplin’s studio manager, Alf Reeves, was also present.

Three months after this meeting, on December 30th 1929, Churchill published some of his impressions of Hollywood, which he called the “Peter Pan Township”, and of Chaplin in particular, in the Daily Mail: “The apparition of the ‘talkies’ created a revolution among the ‘movies.’ Hollywood was shaken to its foundations. […] Alone among producers Charlie Chaplin remains unconverted, claiming that pantomime is the genius of drama, and that the imagination of the audience supplies better words than machinery can render, and prepared to vindicate the silent film by the glittering weapons of wit and pathos. On the whole, I share his opinion.”

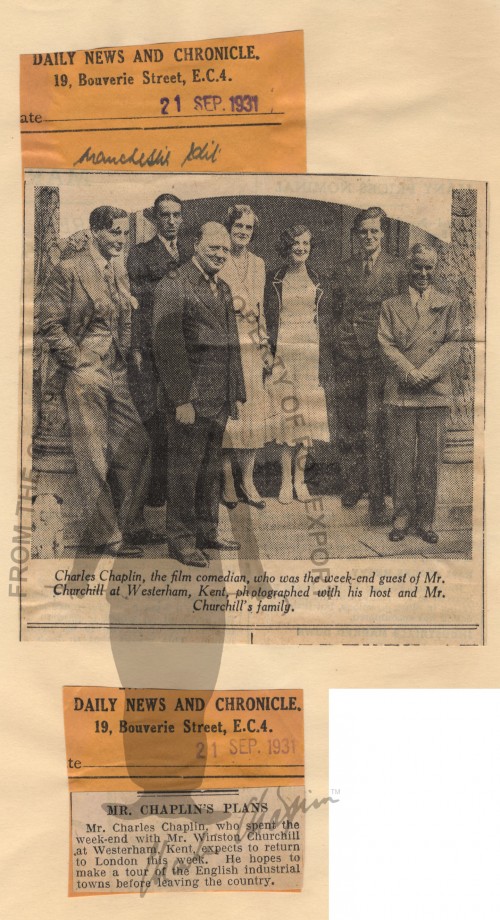

On February 25th 1931, just six days after Chaplin arrived in England for the London premiere of City Lights, he dined and spent the night at Chartwell, Churchill’s home in Kent. Two evenings later, on February 27th, the two men were photographed together at the dinner after the première, where Churchill proposed a toast to Chaplin, “a man who had started out as a lad from across the river and had achieved the world’s attention.”

Later that year on August 14th, Chaplin and Churchill dined in Biarritz, and on September 19th, Chaplin spent a weekend at Chartwell.

In A Comedian Sees the World, Chaplin’s memoir of his 1931-32 world tour, he recounts: “[Churchill] told me he had read that I was considering making a picture of the life of Napoleon. ‘You must do it,’ he said, ‘Apart from the drama, think of its possibilities for humor. Napoleon in his bathtub arguing with his imperious brother who’s all dressed up, bedecked in gold braid, and using this opportunity to place Napoleon in a position of inferiority. But Napoleon, in his rage, deliberately splashes water over his brother’s fine uniform and he has to exit ignominiously from him. This is not alone clever psychology,’ said Mr. Churchill. ‘It is action and fun.’”

Much can be learnt about the admiration Churchill held for Chaplin, and perhaps surmised about their friendship, in Churchill’s article about Chaplin entitled “Everybody’s Language”, in Collier’s, published on 26 October 1935:

"[Chaplin] owes his unrivaled position as a star to the fact that he is a great actor, who can tug at our heartstrings as surely as he compels our laughter. […] And the real Chaplin is a man of character and culture. As Sidney Earle Chaplin put it, when interviewed at the tender age of five, ‘People get a wrong impression of Dad. It’s not good style to throw pies, but he only does it in the films. He never throws pies at home.’”

In London, The Great Dictator opened on 16 December 1940, at the height of the Blitz, when Hitler was a very real and present enemy. The British seemed to delight in Chaplin’s ridicule. Two days earlier, the prime minister himself enjoyed a pre-release screening, laughing especially at the Hynkel – Napaloni food fight sequence.

Years later, in 1952, after screening Limelight privately at Chartwell, Churchill sent Chaplin this congratulatory letter:

A few years later at the Savoy Grill in London, the two met one last time. They had not seen one another since 1931 and Chaplin felt that “Sir Winston was nursing a grievance” because he had not responded to Churchill’s 1952 letter. Apologetically, Chaplin explained that he did not think the letter called for an answer.

Churchill replied, “I always enjoy your pictures."

In 1960 Chaplin cited on Swiss radio the geniuses he had met in his lifetime. There were only three: pianist Clara Haskil, Albert Einstein, and Winston Churchill.